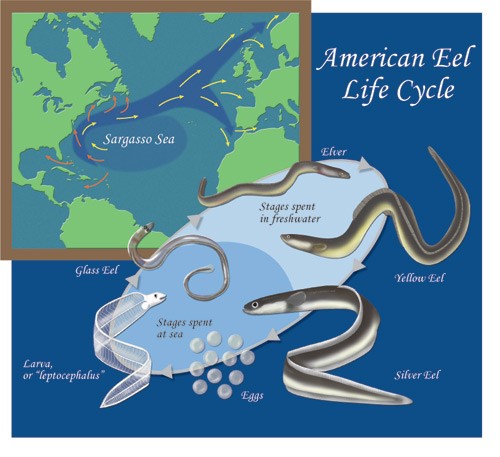

After more than a century of speculation, researchers have finally proved that American eels really do migrate to the Sargasso Sea to reproduce.

A team supervised by Professor Julian Dodson of Université Laval and Martin Castonguay of Fisheries and Oceans Canada reports having established the migratory route of this species by tracking 28 eels fitted with satellite transmitters. One of these fish reached the northern boundary of the Sargasso Sea, the presumed reproduction site for the species, after a 2,400 km journey. Details are published in the latest edition of Nature Communications.

The discovery puts an end to more than a hundred years of conjecture regarding the migratory route and location of the only American eel reproduction site. “Eel larvae have been observed in the Sargasso Sea since 1904, suggesting that the species reproduced in this area, but no adult eels had ever been observed in this part of the Atlantic Ocean,” explained Professor Dodson of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Université Laval.

The many expeditions aimed at catching eels in their mysterious gathering site have all failed, but the recent development of sophisticated satellite transmitters opened up new opportunities for researchers. Julian Dodson and his team affixed these transmitters to 22 eels captured in Nova Scotia and 16 from the St. Lawrence Estuary. In the ensuing weeks, 28 of these transmitters resurfaced in different areas of the Atlantic and transmitted the data they had recorded.

Analysis of the data revealed that all the eels adopted similar migratory paths and patterns. Near the coastline they appear to use the salinity level and temperature to find the high seas. A single eel provided data for the ocean segment of the migration. Its transmitter showed that it turned due south upon reaching the edge of the continental shelf and headed straight to the Sargasso Sea. In 45 days, this eel captured in the province of Quebec covered 2400 km. “This points to the existence of a navigation mechanism probably based on magnetic field detection,” asserted Professor Dodson.

Julian Dodson remains cautious about drawing premature conclusions from some thirty eels, only one of which traveled the full migratory route.

“Our data nonetheless shows that the eels don’t follow the coastline the whole way, they can cover the route in just weeks, and they do go to the Sargasso Sea.

We knew that millions of American eels migrated to reproduce, but no one had yet observed adults in the open ocean or the Sargasso Sea.

For a scientist, this was a fascinating mystery.”

SARGASSO SEA

Mats of free-floating sargassum, a common seaweed found in the Sargasso Sea, provide shelter and habitat to many animals. Image credit: University of Southern Mississippi Gulf Coast Research Laboratory.

The Sargasso Sea is a vast patch of ocean named for a genus of free-floating seaweed called Sargassum. While there are many different types of algae found floating in the ocean all around world, the Sargasso Sea is unique in that it harbors species of sargassum that are ‘holopelagi’ – this means that the algae not only freely floats around the ocean, but it reproduces vegetatively on the high seas. Other seaweeds reproduce and begin life on the floor of the ocean.

Sargassum provides a home to an amazing variety of marine species. Turtles use sargassum mats as nurseries where hatchlings have food and shelter. Sargassum also provides essential habitat for shrimp, crab, fish, and other marine species that have adapted specifically to this floating alga.

The Sargasso Sea is a spawning site for threatened and endangered eels, as well as white marlin, porbeagle shark, and dolphinfish. Humpback whales annually migrate through the Sargasso Sea. Commercial fish, such as tuna, and birds also migrate through the Sargasso Sea and depend on it for food.

While all other seas in the world are defined at least in part by land boundaries, the Sargasso Sea is defined only by ocean currents. It lies within the Northern Atlantic Subtropical Gyre.

The Gulf Stream establishes the Sargasso Sea’s western boundary, while the Sea is further defined to the north by the North Atlantic Current, to the east by the Canary Current, and to the south by the North Atlantic Equatorial Current. Since this area is defined by boundary currents, its borders are dynamic, correlating roughly with the Azores High Pressure Center for any particular season.